In 1875, the whole of Portugal and in particular the Algarve was challenged by a continuing drought.

Most farmers in the Algarve were smallholders whose subsistence agriculture required production of food for the farmer, his family and for his livestock, and also the production of enough seed for sowing the next year.

Non-existent rainfall and drought, therefore, posed a threat to the life of all animals, even humans, through both thirst and hunger.

The Gazeta do Algarve had reported already in 1874 that the drought ?€?sterilised our fields, destroyed important irrigation systems, and dried water sources which had never before been known to fail.?€?

By April 1875, the same newspaper reported that ?€?we are heading towards a frightening food crisis ?€? and there is no longer any hope that agriculture will produce enough to sustain the inhabitants of the province, nor will there be enough pasture to feed the cattle?€?.

Much seed failed to germinate because of the dry conditions, and many trees were dying through lack of water, and especially affected were the fig trees, which were essential to the regional economy. Their loss affected not only the current year, but also potential production for several future years.

The Civil Governor visits

Alarmed by these reports, on May 15, 1875, the Lisbon government ordered the Civil Governor of the Algarve, Jos?? de Beires, to make a personal tour of the region to assess the damage caused by drought.

It is difficult for us nowadays to imagine the conditions of his journey. There was no railway; few roads were metalled; most were tracks; and some were no more than footpaths.

He visited every municipality in the region before returning to Faro on June 10. In each municipal town, Beires met the councillors, the biggest taxpayers, the governors and the parish priests.

He personally saw the gravity of the situation in the Algarve, and his visit resulted in a detailed report, which he sent to the government in Lisbon on June 17 that year. He was able to describe the agricultural, economic and social situation from personal experience.

Vila do Bispo and Aljezur

Governor Beires set out on May 23, and began his tour in Vila do Bispo, known as the granary of the Algarve.

In the parishes of Budens, Raposeira and Vila do Bispo, the wheat fields had appeared magnificent at the beginning of the year, especially those fields more inland.

The drought prevented the development of the wheat crop, much of which had died, and farmers expected a yield of only half of normal. In the parish of Sagres, the damage to the wheat crop was greater. The garrison of Sagres fortress had to transport drinking water from Vila do Bispo, six kilometres distant.

Drought had stunted the olive and orange trees at Aljezur and Odeceixe, and wheat production was down by a third on a normal year. Wet land which had been used for rice production now accepted only one sowing of wheat, and the harvest would be reduced by a third compared with a normal year. Many people had already left both districts because of the lack of drinking water.

Lagos and Monchique

Lagos was normally the largest producer of figs in the Algarve, and an important producer of almonds, but this year the trees had barely budded, and the yellowing leaves were already falling.

The council estimated production at a quarter of normal, and one large local producer estimated his current losses at more than 1.000$000 reis (about ??80,000 at today?€?s values).

Coastal parishes suffered worse damage. In Luz, most fruit trees had died and the cereal production was catastrophic, and in Odi??xere there was little hope of harvesting even twice what had been sown.

In the parish of Lagos itself, most of the trees had died, and there was no straw from the wheat fields. Vegetable gardens were also affected catastrophically. Although the fig trees of inland Bensafrim were not dying, they were not fruiting, and cereal production was down by a third.

The chestnut, orange and pear trees of mountainous Monchique were normally irrigated from the many springs in the area. But the winter rainfall had been half its normal amount, and some trees had already been lost through drought, nor were the farmers in Alferce and Marmelete able to irrigate their crops as needed.

Portim??o

The traditional orchards of Vila Nova de Portim??o ?€? almond, fig and carob ?€? were already losing their leaves. The spring sowing of wheat was not even producing straw, and there was no production of hay for cattle feed.

There was a similar story in Mexilhoeira Grande and Alvor, where production from the remaining fig and almond trees was at a twentieth of the usual, and the olives had already lost their flowers. The people of Portim??o had no wheat, oil or nuts, nor forage for the animals. Their position was precarious.

Lagoa

As the road bridge was not finished until 1876, on May 31, the Governor crossed the Arade by ferry. Lagoa had the most intensive agriculture in the region, particularly in figs and cereals, but its fruit trees were already bare.

Because the soil of coastal Ferragudo was generally thin and arid, this parish was in the most deplorable condition. Figs and almonds were its main crops, but most had already been lost, and the wheat did not form any grain at all.

Porches and Est??mbar were in a similar state, and production was at around a twentieth of normal. The olive trees had flowered but had not fruited, and many fig trees were near to dying.

Silves

In the parishes of S??o Bartolomeu de Messines and Silves itself, farmers predicted a fig harvest two thirds of normal. The olive trees of Algoz were barren, fig trees were producing only about a quarter of normal, vegetable gardens were completely dry, and the vines and carobs were failing. Of the two wells in the parish, one was dry and the other nearly so. The vines in Alcantarilha were doing well, but P??ra was in a worse state than any other parish.

Albufeira

The neighbouring coastal municipality was similarly dry. At Paderne, many of the fig trees had already died and, if conditions did not worsen, the best harvest would be a quarter of the normal. The olive trees had no fruit at all, the almonds were badly affected and carob production was of poor quality.

The late cereal crop was totally lost, and although the vines had produced grapes in quantity, the fruit was falling.

Loul??

In the municipality of Loul??, the hill parishes had suffered less damage, while those nearer the coast were in a miserable state, and subsistence farmers were in great difficulty.

The farmers of Salir and Ameixial expected a cereal harvest little worse than that of a normal year, and while the carob and fig trees had suffered little, the olive trees were producing nothing, the water sources were drying up, and animals were dying for lack of pasture.

Most of the ground in Alte was not cultivated, and the carob trees were producing less than in a normal year, but the late sowings were reviving after recent showers. Queren??a?€?s olive trees also had no fruit, and the carob trees promised little. The grain crops had all failed, and the cattle were dying for lack of pasture.

Tavira and Castro Marim

Although Tavira suffered less than other municipalities, production was still at only a fifth of normal. The main crop in Santo Est??v??o was olive and carob, both of which were failing. The few figs and almonds and vines were in a poor state, grain production was at a third of normal, and the water sources were drying up.

In Santa Catarina da Fonte do Bispo, the main product was olive and carob, which were both failing, and whereas the grain crop was about half of normal, that in Cachopo in the mountains was near normal.

In spite of its coastal location, Fuzeta did not suffer greatly in this dry year. Vines were its main crop and had much fruit, and the figs were much healthier than in other locations. The grain crop was adequate, and the late sowing was not altogether lost.

The fig trees in the parishes of Concei????o, Santiago and Luz promised a reasonable crop, and the grain crop was in better condition than that of Santo Est??v??o, whereas the grain crops of Santa Maria were producing little more than the seed for next year.

In the parish of Odeleite, there was little potable water, and although Azinhal?€?s orange plantation was in good condition, the vines were mostly ruined. Many of the fields near Castro Marim were contaminated by brackish water and the only crop doing well was carob.

Summary

The coastal municipalities of Portim??o, Albufeira, Lagoa and Faro were in the worst state, and agricultural production was severely affected, while the production of the hill parishes of S??o Marcos da Serra, Ameixial, Cachopo and Gi??es were scarcely affected at all.

As for the people of the region, Beires divided them in three categories: the seafarers were the poorest but suffered least in the drought, since the fisheries were plentiful.

Daywagemen were little affected since there was both public and private employment, and the cost of food was relatively low. The worst affected were the smaller landowners, because they had no seedcorn and had to sell their animals at a low price since they were unable to feed them. Many had left already to look for work in Lisbon.

Governor Beires finished his report on June 17. In it, he recommended various public works for employment: construction of the railway to Faro; building roads; and the supply of seedcorn to farmers.

After commissioning the report from Governor Beires on May 15, and receiving the finished report on June 17, the government began remedial works as soon as July 1, only six weeks after the initial instruction. A very rapid reaction!

The government immediately commissioned work on the railway from Faro to S??o Bartolomeu de Messines and four or five other road works. It also sent four pumps to be used where the water resources were lacking. Over the following months, various ships called in the Algarve bringing seed for the various crops ?€? wheat, barley, beans, maize and oats.

A few showers fell in June, but the drought persisted, and the Gazeta do Algarve reported that no-one could remember such a natural disaster. It called 1875 the year of famine.

The floods

In contrast to the drought of the summer of 1875, the floods of December 1876 were unprecedented. Following an unusually wet October, continuous rain in the first week of December caused the River Guadiana to rise an astonishing 25 metres, and the floods in villages on both banks claimed many lives. A similar flood of the Arade in Silves caused numerous buildings to collapse.

In retrospect, the sudden change from drought to floods in the two years was remarkable, and we can only imagine the suffering of the people involved in both disasters.

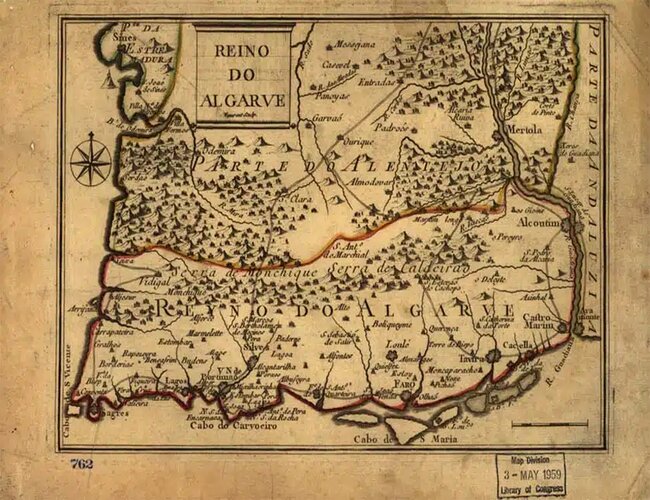

Material for this article has been drawn from a series of articles written by Aur??lio Nuno Cabrita and published in Sul Informa????o in July 2017. Images show postcards of the Algarve taken in the late 19th century and early 20th century.

By Peter Booker

|| features@portugalresident.com

Peter Booker co-founded with his wife Lynne the Algarve History Association.

www.algarvehistoryassociation.com